| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| cable at the crossroads |

|

(originally appeared in Barron's November 11, 2002)

Barron's

Other Voices

Creative

Destruction

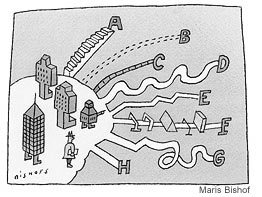

These are turbulent times for the cable industry. Long undercapitalized and led by free-wheeling, iconoclastic empire builders, the cable industry is struggling with the end of an era of significant new subscriber growth. Many investors view cable as a mature business with the potential for squeezing out only marginal returns. Cable, however, has moved far more aggressively onto the Internet than the big phone companies, which are only now seriously rolling out DSL, their own version of broadband access. Even as the cable operators have lost revenues to satellite TV they have compensated by boosting sales of cable modems. Many of the industry's investment dollars are flowing into development of a next-generation set-top box -- and the massive infrastructure behind it -- that supporters see as the central control point for the wired home of the future, and as a way to sweep telecom dollars into cable-industry coffers. It is a tough period and a very dynamic one. But if cable operators were to step back and examine longer-term trends, they would perceive a far more forbidding future. In fact, most cable companies are dead on their feet. Their grim fate will become obvious in five years and that fate will be well on its way to reality in 10 years. Only the cable operators that perceive the trends early enough and act in time have an opportunity to survive and achieve some success. There is probably even room for one great company to emerge out of the cable industry -- as the foremost champion of wireless broadband ethernet to the home. To understand

what is happening, observe the trajectories of two long-term trends (see

chart). They show that the ability to compress data is improving, and

the average speed of data coming into the home is increasing. Around 2004,

those two trend lines will meet. At that point, sending TV-quality images

directly to the home over the Internet will be simple, and a historic

business barrier will fall. A few content providers then will say, "Cable systems are a thing of the past. You consumers ought to dial in and get your videos and your TV shows directly from us." Others will follow more slowly. A decade after the lines intersect, virtually all content providers will have found many ways around the less-than-beloved cable middleman. Film studios will be advertising and delivering movies directly to consumers. News organizations will provide broadcasts that consumers can download at the hour they find most convenient. And sports teams will end their long-term cable contracts and reach their fans more directly -- and more profitably -- than today. The main reason cable gained leverage with content providers in the first place was its status as a local monopoly. That leverage has dissipated somewhat with the competition from satellite TV. But direct access to consumers by content providers will undermine that leverage completely. Loss of fees from transmitting content-advertising dollars alone are a third of total industry revenue-will drive cable into the red. The cost structures that are built into the industry will prove too difficult to revamp fast enough, and much of the industry will simply cease to exist. Many businesses facing such long-term trends retreat to a state of self-denial. In the early 1990s, AT&T management argued internally that the steady upward curve of Internet usage would somehow collapse. The idea that it might actually overshadow traditional telephone service, was simply unthinkable. But the trend could not be stopped -- or even slowed -- by wishful thinking and clever marketing. One by one, the props that held up the long-distance business collapsed. First time-of-day pricing, then fax machines in the wake of e-mail, then profitable stand-alone services fell prey to low cost, always-on, fixed-priced data services from companies with new names and little brand equity. In other words, as the leverage that came from AT&T's former monopoly status diminished, so too did its ability to control its customers. Indeed, so quickly did the business model for long-distance service providers collapse that the entire industry has been transformed into little more than a feature in a larger communications set. In video compression and transmission speeds to the home, we are dealing with classic cost-improvement curves. Such curves represent the interactions between market and scientific disciplines, and they are very predictable. Experience shows that if new technologies promise improvements by a factor more than four, they tend not to get funded because they are seen as too risky. And if they

promise less than a factor of two, they tend not to get funded because

they offer too little economic benefit. So each new generation of products

-- be they jet engines, software or chicken broilers -- brings about a

measured, highly predictable benefit. Thus the curves determining cable's future stretch out for all to see. And as the modems cable companies are so energetically promoting grow ever faster and ever cheaper, the cable companies will find that they have unintentionally cut themselves out of the content delivery business. Customers will simply bypass the cable operator's content -- and its layers of fees -- and go straight to the source. What cable companies must do is become transport companies. A smart cable company would stop pouring money into projects that conflict with the new reality and have repeatedly failed to gain traction in past trials. The hundreds of millions of dollars being invested in set-top-box entertainment hubs would flow elsewhere. In the coming era of direct contact between content-providers and consumers, the set-top box will no longer be required as a mediator for information. No amount of additional set-top box features can change that fact. Instead, the open standards of the Internet will dominate -- and a range of network-attached devices will be made and sold direct to the consumer by consumer-electronics companies. A smart cable company would focus all available investment dollars on finding new ways to becoming a better pipe company -- facilitating the streaming of video through the cable modem, for example, so that true TV-quality on the computer screen becomes dependable. The present cost structure of the cable industry remains way out of line for such a model. Yet as cost-efficient pipe providers, cable companies would be well-positioned to fight off the local phone companies, who will almost certainly continue to suffer from lethargy and capital inefficiency in defending their voice services. Even with a full-blown crisis for cable years away, it is clear that only the most efficient users of capital will win. In addition, those cable companies with ambition reaching beyond managing dumb pipes have one very exciting option: The creation of a nationwide wireless ethernet network based on 802.11, or WiFi. The cable operator would move from a proprietary, private wired network to an open-standard, publicly-accessible wireless network simply by installing wireless ethernet base stations on the cable network running down the street. Customers would utilize the inexpensive receivers already being bundled in their home and business computers, and soon bundled into their CD players and televisions, allowing the worlds of entertainment and information to meld seamlessly. Customers would pay their monthly fee and access the network by entering their passwords. They could access all their video, voice and data needs anywhere -- at home, in their backyards, in hotel rooms or airports. From cable's perspective, the beauty of such an approach would be its low, shared capital cost combined with wide reach. Cable companies could leverage their existing customer set and infrastructure. The most economic solution, after all, is to end wiring at the street and broadcast to a network of customers. Cable companies are at least 90% of the way there now. Moreover, in adopting 802.11, they would have the advantage of adopting a wireless standard for which all the expensive research and development has already been done and codified on somebody else's dime. It's an approach that is uniquely suited to cable's present strengths. No competitor is likely to move anywhere near fast enough to head off a focused cable company. And it may be one of the few possible paths such a company has open for survival. Now all that is needed is for some cable company leader to paint a credible future that excites the passions of Wall Street.

|

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |