| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| 'tis the season to be caulking |

| Dec 2022 |

|

Caulk is the devil's plaything. It blocks driving rain from slipping behind a window frame. Seal tubs and tiles from mold. And hides a multitude of goofs and errors from view- from badly coped joints to gouges and cracks. Caulk is both a friend to professionals and a crutch to the weekend warriors. But caulk has an Achilles heel. It can stretch, but only so far and then it cracks or splits. Caulk seals and spans. Providing the surface is carefully cleaned1, and an appropriate chemistry identified, sealing is often trouble-free. But "spanning" is another issue entirely if the spanned gap moves with time and temperature. How far can you stretch caulking before failing? Well, a bead of fresh silicone caulk might stretch (and recover) by 300%, and latex by nearly 100%. That's in the lab. In the real world, performance is actually closer to 50% and 20%. Why? Well, caulking ages and dries out and may shrink. It stiffens in the cold and softens in the heat. It's exposed to cleaning solutions, sunlight, water and scratches. When stretched, those scratches explode into cracks, in the same way the nick on the top of a ketchup packet concentrates forces so you can easily rip open the foil. Here's a picture of a facade on a local building where the caulking split open after a few seasons. Where the elastomer was originally flexible, it's now stiff and brittle:

What about caulking at home, where a countertop meets a backsplash, or a cabinet the wall? Houses move with the seasons and wood shrinks as it dries. It's not unusual for a gap to appear in the winter and shrink in the summer. For example, this brown cabinet pulls away from the wall every year by a penny's thickness, along with the granite top. Note the silicone caulking even failed in spots where it did not adhere1 to the granite (not to mention that paint won't stick to silicone and cracks-off with every seasonal swing).

How can we avoid these problems? Simply by minimizing stretching. Caulking will split open if stretched too far, but can withstand huge amounts of compression without failing. If a crack appears when compressed, it is squeezed closed by the pressure (e.g. the same principle behind tempered glass). So we need to configure the gap so it either compresses the caulk instead of stretching, or if it has to stretch, never by more than say 25%. Achieving these two goals can be tricky, and often violates common sense. Did you know it matters what time of year you caulk? For example, if the gap opens and closes annually, WAIT until the gap is widest and THEN caulk. In this way, when the walls move the caulk is always under compression and won't crack. Instead, the caulking bead will bulge out slightly when compressed, returning to flat a year later.

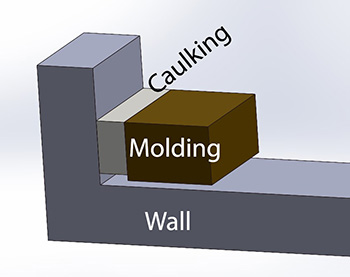

If there is no way to prevent the caulk from stretching, minimize the percentage length change. Which often means a larger, rather than a smaller, bead of caulk. For example, if the house moves annually by 1/8" of an inch, the caulk's width should be at least a half inch so the percent change is around 25%. Unfortunately, most weekend warriors blithely run a narrow bead of caulk directly over the gap to neatly hide the fissure, so the percent change is closer to 100%. No wonder it splits open every year. A few simulations illustrate the problem. Imagine filling the gap between crown molding and the wall with a narrow bead of caulking:

(Solidworks, using hyper-elastic materials adjusted to match latex-caulk blend) And then imagine the wall expands by the same amount as the original gap. Say an 1/8" fissure that opens by another 1/8". Not uncommon. The caulking will stretch and neck in the center. Enormous stresses will concentrate along the caulk's perimeter where it is pinned to the adjacent surface. These interface stresses may even rip the caulk off the molding, especially if the chemical bond was weak.

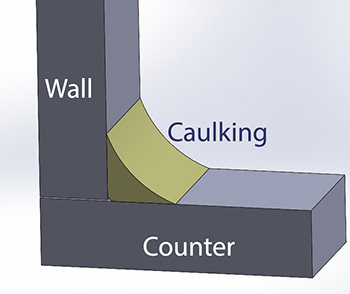

In this simulation a BLUE color indicates low stress regions where the caulking will fully recover after each cycle. RED means the caulking will split and tear, with the rest of the rainbow spanning between these two extremes. (100% change in caulk length between molding and the ceiling) On the other hand, if the gap AND the caulk were much wider to start, the percentage change after a 1/8" expansion would be small, and the caulk would remain elastic: (25% change in caulk length between molding and the ceiling) Note in this example the caulk is free to move along its entire length. So the only stresses are at the attachment points. Commercial buildings specify wide expansion joints for exactly this reason (see this excellent resource from the Adhesive Sealant Council). What happens if the caulk fills the entire gap, like in a corner?

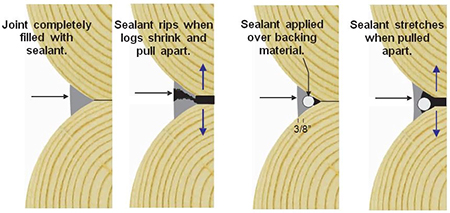

Now we've trigger a critical situation- the caulk in the exact corner might have to stretch by more than a hundred times to keep up with the wall's motion. Naturally, it will fail at this point and the resulting tear is likely to propagate to the surface. Even in this simulation, where I rounded the corner slightly, the caulk will fail as the bead is tugged upward: One solution is to exclude caulk from entering this danger zone. A "backing rod", e.g. a soft foam rope, could be jammed into the corner. The caulking then forms a tent from wall to counter which is so long it can accommodate any motion. In fact, log homes are sealed with with thick layers of caulking and a backer rod. Remarkably, logs can shrink by up to an inch, so this simple precaution is a critical best practice:

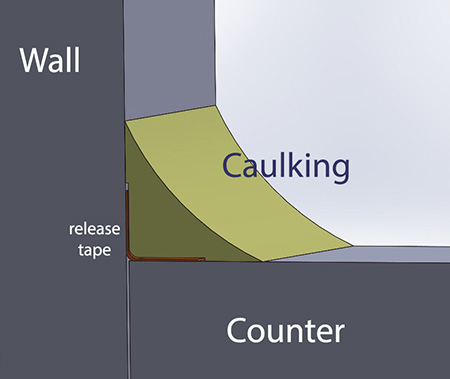

Another alternative is "bond breaking tape". This tape is sticky on one side (to adhere to the wall and counter) and slippery on the other (so the caulking doesn't bond). Press the tape into the corner and cap with a bead wider than the tape:

A simple but effective solution: People don't always appreciate the look of a wide caulk bead. Frankly, on countertops I suggest gluing the backsplash directly to the countertop and free of the wall, so they move as a unit. Even a thin caulk bead can then safely seal a gap that never opens. Molding is a tougher case, especially on exterior walls. You can open the preexisting gap from a 1/16" to a 1/4" inch, then caulk during a season where the gap is widest. Or, treat the molding and cabinets like a breadboard, and allow them to float so they don't bow outward. Or, attach the cabinet to the wall and the molding to the ceiling, and let them slide past each other. Details matter.

|

|

1 Professionals and amateurs alike treat caulking as if it were some kind of magic salve, able to heal all wounds. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Caulking is squeezable chemistry, which must be analyzed and quantified. For example, many people mistakingly extrapolate the superb mechanical properties of silicone caulk to assume it can stick (just as superbly) to any surface. In fact, silicone is rather poor in this regard. It adheres tenaciously to glass, very well to glazed ceramics, ok to smooth granite, sorta to marble and wood, and peels right off of acrylic (as my students building a plexiglass water tank soon discovered). It also tears, scavenges dirt and absorbs cleaning chemicals. Cured silicone rubber repels water AND fresh silicone. For this reason it is very hard to re-caulk a tub that was previously silicone caulked- even a thin residue of old silicone caulking will prevent adhesion. In fact, surface preparation is a key and sadly ignored step. Wet sticky pizza dough glides easily over a counter-top dusted with flour or oil. The same is true of caulk, which will not adhere over greasy finger prints, old caulking, soapy scum, grout residue or even dust. Surfaces must be wiped clean, sometimes with soapy water or water jet in the case of brick and concrete, then wood alcohol and perhaps acetone, and dried. Primed wood accepts caulk more readily than bare, especially end grains where the caulk might be loosely suspended on the highest grain protuberances. Always read the manufacturer's data sheets- it will list compatible bonding surfaces. They frequently sell primers to improve adhesion to difficult materials. A few caulk chemistries may stick to wet or cold surfaces, others will cure into a floating rubber snake that slithers away under pressure.

|

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |