| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

|

Gerrymandering is a necessary evil Absent multi-member districts, gerrymandering is the DEMOCRATIC solution of FIRST resort |

| july 2017 updated Jan 2023 |

|

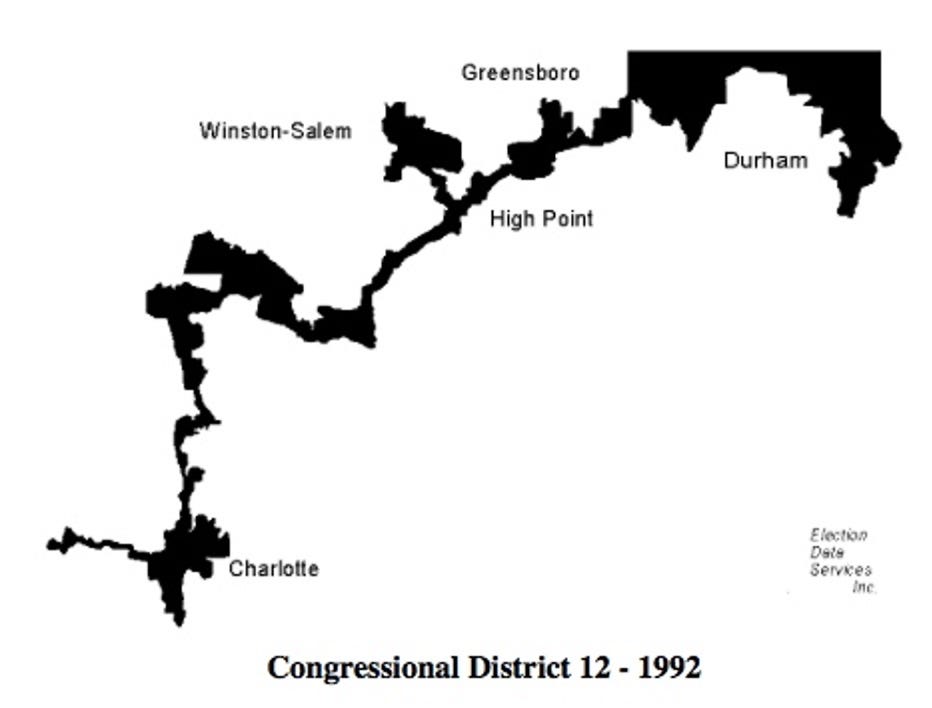

By now almost everyone is aware of the evils of gerrymandering. Where the majority party draws a congressional district solely to benefit their own agenda. Or to disenfranchise people who are not like themselves. At its most blatant, gerrymandered districts might look like this tortuous, 160-mile-long ink blot connecting five cities:

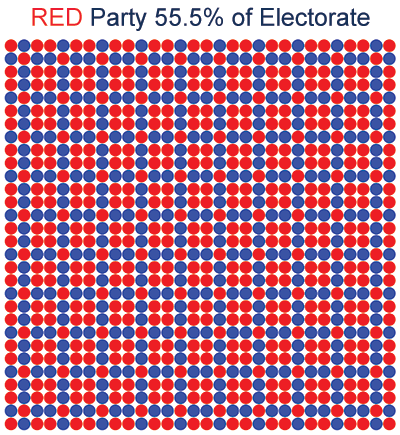

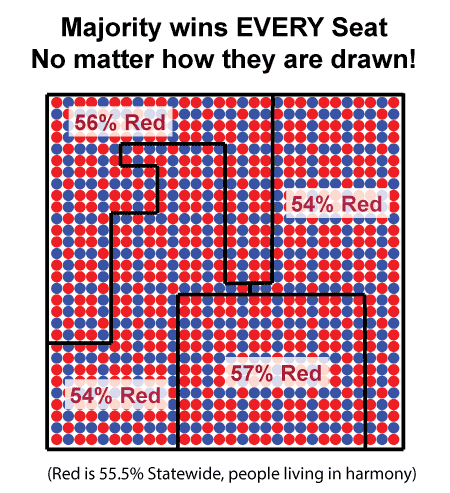

But why not adopt the obvious remedy? Just mandate compact redistricting by law, and the mischief will end. Stopping gerrymandering in its tracks. Unfortunately, you may not be aware that compact maps are just as easily manipulated for political gain as a district that looks like a cracked mirror. Even more surprisingly, to guarantee an elected legislature proportionately reflects the views of its citizens, you must settle near kindred spirits, live in an echo-chamber, and gerrymander- or risk disenfranchisement! Really? Compact districts can be unfair? Gerrymandering is good? To understand why, imagine you reside in a harmonious Eden where we respect each other’s differences and live peaceably side-by-side. Perfectly desegregated. With both parties spread uniformly across the state: Since RED neighbors slightly outnumber BLUE in this state, a fair and representative outcome in a four-district contest elects two RED and two BLUE congressmen, or perhaps three RED and one BLUE. But when people’s interests are this uniformly distributed, EVERY district outline, no matter how compact or jagged, leads to the same outcome, RED ALWAYS WINS!

Surely this artificial, regular pattern of voters must be the problem. How does redistricting operate when the voters are randomly distributed? As before, no matter how compactly districts are drawn, a majority party’s tiny numerical advantage snowballs into winning every election:

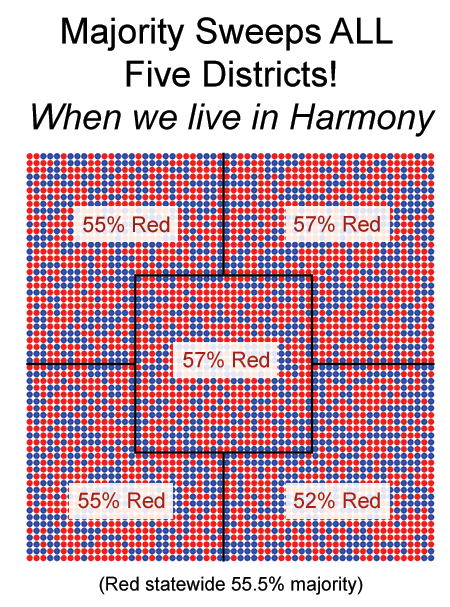

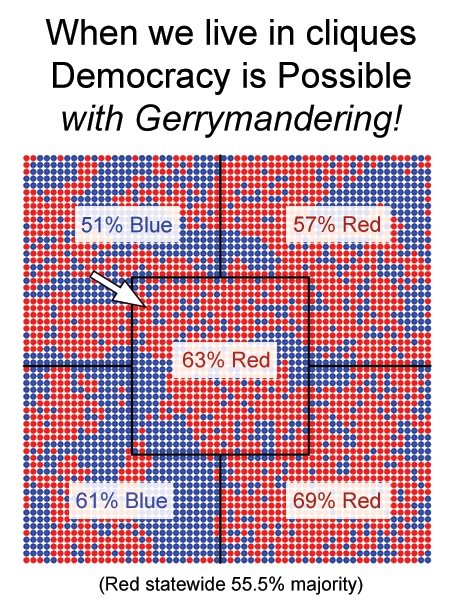

Clearly a perverse outcome. In this mythical paradise, BLUE citizens are NEVER able to elect their own representatives! Even with compact districts, by living shoulder to shoulder they suffer under a Tyranny of the Majority. Still, we don’t frollick in a mythical Eden. For economic, social and historical reasons, people tend to reside near others like themselves. Farmers near farmers, rich near rich, democrats near democrats, ethnic groups near ethnic groups. Excluding the “other” is a good thing. By living and working together in a community of shared values, citizens enjoy numerous tangible and emotional benefits. Common language, common goals and common virtues. Strong, stable local institutions advance the public good, and should be encouraged. To a point. Now imagine we segregate into more realistic, intermingled cliques (note the RED and BLUE clustering). In this example (with the same compact districts as before), the voters now elect three RED and two BLUE legislators:

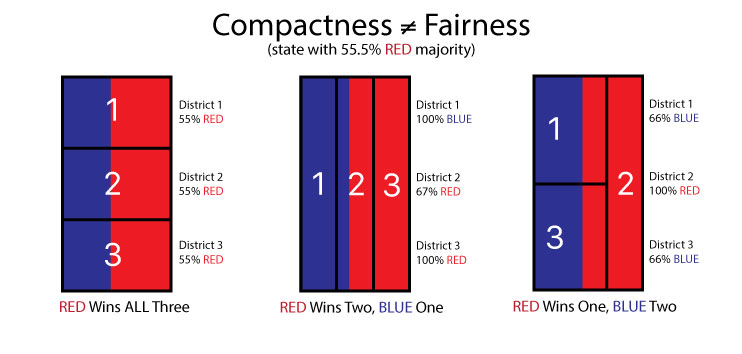

A pretty fair outcome. But sometimes the clusters don’t line up with existing districts or natural geographic boundaries, and once again BLUE loses every contest. Clustering is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition to guarantee a representative election. District borders matter. Here is a simple, though extreme example of complete geographic clustering by party. RED will win one, two or three seats, depending on how the cake is cut:

It pays to be the person holding the knife… Without an independent commission setting the criteria, you can imagine the immense temptation for RED legislators to slightly tweak the center-district’s boundary (near the white arrow, one drawing above). Just by interchanging a few voters across the border, while continuing to proclaim adherence to a smooth and “fair” outline, BLUE loses another seat. Upon gaining power, the winners may further tilt voting laws and districts in their favor, locking in a permanent advantage, undermining any positive benefits of redistricting. And if a bit of tweaking won’t do, you can always blaze a crooked trail between islands of RED supporters to win the district. Independent commissions are essential, but problematic tradeoffs and value judgements abound. At the macro level, what do we mean by a “fair” apportionment? Optimizing district boundaries so the percentage of two-party winners coincides with party registrations? Or rearranging district borders so a third party can win? In other words, is this merely a “two-party political question” and all that matters is party equanimity? Perhaps “fair” means ignoring parties but making sure at least one district can elect a Black or Hispanic candidate? Such deference is required under the Voting Rights Act. If not race, perhaps natural community boundaries like rivers or city wards deserve top priority. Advocating gerrymandering as a remedy for the “tyranny of the majority” places the government in the tenuous and dangerous position of blessing certain communities of interest above all others. Seeking equal protection through unequal treatment. But sometimes we have to put our finger on the scales of justice. These independent commissions face tough challenges balancing so many diverse criteria, especially if they are uncorrelated. A Sisyphean ordeal tweaking the shape of a small number of districts to satisfy every petitioner. Fortunately, once again the echo-chamber effect comes to the rescue. For example, evangelicals tend to vote Republican and live outside cities, so religion is often one less independent principle to manage. Or manipulate. Unquestionably, Americans recoil at allocating a fixed number of seats along religious or ethnic lines, as mandated by other nation’s constitutions¹. OTOH, by not choosing race, sex, political party, etc. as THE standard for evaluating a “fair” district boundary we risk a similar anti-democratic outcome. In fact, as we discuss in the TL;DR endnotes,disenfranchisement is the norm and deference to political parties far outweighs the democratic voice of the people. For now, the most democratic and pragmatic re-districting methodology appoints independent commissions to assign district boundaries respecting communities of interest while balancing political and social cliques in rough demographic proportions. They do the best they can.

But we can do better. One proven alternative replaces geographic single-member districts with proportional² at-large elections. While at-large voting has a long history in the US, it languished after a series of Apportionment Acts starting in the 1840’s. Partly to blunt the rise of cities by protecting landed interests, and partly overt racism. Crucially, when multiple seats are in play the government no longer is in the business of carving out protected categories. Instead, fluid interest groups (say gun owners or recent immigrants) can unite behind one candidate in the field, and by voting in aggregate, put them over the top³. An impossibility with a single candidate. Internationally, multi-member districts routinely promote a more representative government. At-large proportional voting may appear complex, but is potentially fairer than single-member districts, and could deflate much of the partisanship currently blocking Washington from doing its job. In our highly connected world the truism that “all politics is local” has waned in relevancy, but palpable benefits emerge by strengthening local community ties. Internationally there is a trend towards a blended solution- often called “mixed-member districts”- to “split the difference” between geographically focused leadership and wider societal priorities. For example, in a state with six representatives and six districts, we could move to three single-member districts reflecting community values, and three at-large representatives across the state. Or, by increase the size of the House maintain the six existing districts and layer in three new, state-wide at-large representatives?. Responsive democracy for the 21st century.

Endnotes TL:DR

SOME EXCELLENT RESOURCES

[1] Among others, Afghanistan reserves 67 seats for women, India allocates 24% of parliament by caste and tribe, and the UK 26 seats in the House of Lords for Church of England Bishops. [2] At-large elections can be used to suppress minority voting if non-proportional. Consider elections where parties run as slates (common in parliamentary systems, and some US cities). By limiting voting to a slate of candidates that fills every open seat, the majority clique’s slate wins every election, even in a multi-member district. However, in a proportional system the number of candidates elected from the slate is proportional to the number of votes that slate receives. Assuring a minority backed candidate’s rise to the top. Other ranked-choice and proportional systems achieve the same result without slates. [3] We may observe this flaw even in our senatorial races. Under Article 1 Section 3, only one senatorial seat is open in any election cycle, and the entire state functions as a single “virtual district”. Accordingly, the majority party consistently elects both senators, albeit two years apart. But if two senate seats were open at the same time in a proportional voting process, the delegation would even divide by party. The facts are clear. In 2022, a mere7/50 states split senatorial party affiliations (only 4 if independents are not included), and most of these splits are in “battleground states” where there is less than a 5% party affiliation difference. In a two-seat proportional election, the split would be nearer to 50/50, which more closely echoes party divisions in our county. For example, imagine two candidates from the majority party, and one from the minority competing for two open senatorial seats in a proportional election. If the RED party affiliation was 60%, and the BLUE 40% (a 20% difference between parties), the BLUE backers would dedicate ALL 40% of their votes towards their one candidate. The RED could split their vote between their two candidates, and if one received more than 40%, the other would receive less than 20%. Or focus all 60% on one candidate. In either case, RED takes one seat, and BLUE wins one seat. Providing the percentage difference between party affiliations was no more than 33% and the electorate remained disciplined and did not vote split on independent candidates, the state delegation would split by parties. We note the difference in party affiliation in all 50 states is less than 33%. [4] Congress has the power, under its Article I Section 4 “Time, Manner and Place” clause to authorize multi-member districts while permitting each state (the fabled “laboratories of democracy”) to evolve their own proportional voting schema. Then after a decade of experimentation, Congress might later revisit the Apportionment Act to specify the most effective and fair proportional rules. We can also learn from the experience of multi-member state-legislative seats. The mechanics of voting in a proportional multimember district may seem arcane, at first. There are literally hundreds of proposed ranked-choice voting schemes, all with their own individual pros and cons. Then you have to decide if candidates should run as individuals or on party slates. And watch out for people trying game the system by strategic voting for their second and third choice candidates. A tactic made more pernicious by social media hacks. But somehow other democracies have cracked the code.. In a large state like Texas or California, voting for 20 or 30 at-large representatives out of a field of hundreds might tax voter’s cognitive skills. Mostly likely the state would be divided into more manageable geographic regions, each with half a dozen open seats (again raising the possibility of gerrymandering, but it’s a simpler problem for an independent commission to address). Among the myriad of issues with single member district-centric voting:

|

|

|

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |