| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| by the skin of your teeth |

|

Nov 2013

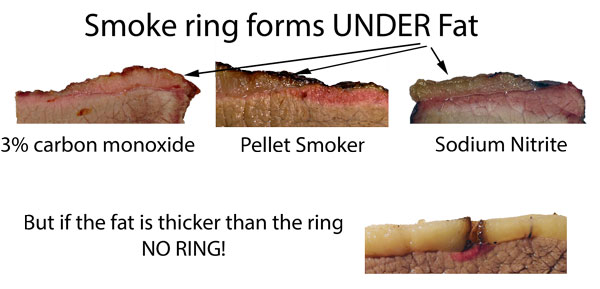

Silver skin (epimysium) is a thin membrane of elastin, wrapping connective tissue such as the fascia, those bands of of white fat and collagen delineating cuts of meat. Think of silverskin as meat's girdle or spanx- helping to lift and separate muscle groups so they can easily slide past each other. Providing support and compartmentalization. The sliver skin is quite thin- on ribs, perhaps a mm or two thick. And when cooked, the elastin sheet is as tough and as indigestible as a cellophane candy wrapper. Some people leave silver skin on when smoking ribs, hoping the membrane will act like a sheet of foil in the Texas Crutch, preventing the meat from drying out. There is a kernel of truth behind this view, although the bones themselves are more effective at blocking evaporation. Still, most people remove the silver skin as a courtesy to their guests, while hoping rub flavors will penetrate more effectively without this barrier blocking the way. But what about smoke? Will silver skin block a smoke ring from forming? Smoke rings are the chemical by-product of nitrites (from properly combusted wood) interacting with the myoglobin naturally present in most red meats. The chemicals which color smoke rings are distinct from those contributing to smoke flavor. Plus they are much smaller- and like tiny salt ions, might be able to slip through the silver skin layer. A thick fat layer, for example, the fat-cap most people leave on brisket for flavor and moistness, is transparent to nitric oxide and carbon monoxide. So a ring will form under a thin fat cap. But, if the fat is thicker than the ring, the chemicals never make it to the meat's surface in time.

How about the silver skin? It is very thin, so thickness is no longer an issue. In this experiment, we removed the silver skin from a rack of St. Louis ribs. Then smoked for 6 hours at 225F on a raised grill in a pellet smoker, flipping occasionally. Only the meat side was rubbed with salt and spices. Before smoking:

and after:

Caramel-colored all around, with a fully developed mahogany bark on the meat side. The smoker was equipped with a water bath- this bath maintains a relative humidity level above 10% during smoking, and high humidity increases the thickness of the smoke ring. This pale pink smoke ring is easily seen in cross section:

But the human eye is poor at distinguishing soft edges (and compressed JPEGs on the internet lose resolution), so in Photoshop I enhanced the red colors in this photo, generating a more distinctive smoke ring:

The first thing you notice is the smoke ring above the bones (top of image) is darker than between the bones. I believe this is the result of the bones blocking more than half the surface area, and thus much of the nitrite, from diffusing into the meat from between the ribs1. The lower the nitrite levels, the duller the color. The ring thickness directly above the silver skin is a half to a third as thick as where the silver skin was removed from the bones. So fascia slows, but does not block, a smoke ring from forming. My presumption is silver skin, which is very tough, is semi-crystalline. And thus very dense and less porous than fat at the atomic scale. A similar effect explains why the original Saran Wrap was so effective at blocking odor molecules from escaping. The PVC wrap was stretched during manufacturing, and this aligned and partly crystalized the PVC polymer. Today, PVC is no longer an accepted plastic film for food contact, and the new clear wrap plastics do not crystalize as easily. Nor do they block odor molecules as effectively... Personally, I always remove the silver skin. It will not block salt from penetrating, nor eliminate the ring. But it will give your teeth a break.

|

|

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 It is also possible muscle groups between the bones have a lower myoglobin level, or that the rub interacts with the smoke to darken the ring. Based on other work this is unlikely, but we will investigate more thoroughly in a future article.

|

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |