| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| it's not the heat, .. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jan 2013

Yet water is even more fundamental. We are born of water. Our flesh (and the flesh of the animals and plants we consume), are more than three quarters water. True, heat breaks down proteins and destroys toxins so our foods are easily digested, but moisture is the universal solvent, ultimately extracting flavor, and controlling how quickly food cooks. So its curious we demand precise control over the heat sources in our kitchen, but rarely over the humidity. To cook a stew, we heat meat in an oven or on a stove top or in a crock pot. But we control it's humidity by simply covering the pan. Temperature varies by recipe, but humidity remains pinned at 100%. To cook bread, we fiddle over convection oven temperatures and thermal conduction from blisteringly hot pizza stones, but humidity is an after-thought. Perhaps we ineffectively develop a crust by spritzing in a teaspoon of water, but the crust may equally well depend on the number of loaves in the oven and their shared evaporation. Or whether the oven is stoked by wood or gas. All proxies for relative humidity. And microwaves? Heat and speed but no humidity control- one reason they are used to warm, but rarely to cook a meal from scratch. Even professional kitchens have been slow to control humidity with the same facility as fire. Some bakeries introduce humidity during the initial stages of bread baking via steam injectors. Fast food restaurants fry their chicken in a pressure cooker to concentrate water vapor pressure, and thus juiciness. But it was only in the 1970s that companies like Rational AG developed the Combi-Oven (combining heat and humidity). With separate controls for temperature and humidity, and more recently, offering computer-programmable units with built-in recipes for common cooking tasks. Combi-ovens are now an essential part of the modern restaurant for everything from turning out the perfect souffle, to pre-heating a steak before grilling, to poaching fish. Today, there are many players such as:

But adding just one new, though essential, variable like humidity geometrically increases the complexity of developing new recipes. Chefs and manufacturers tell me these new tools are still underutilized- their potential marred by lack of familiarity and knowledge of experimental design, so necessary to efficiently test all possible combinations. It will take a while for a new generation of chefs to master their ovens, and for their understanding to filter into the kitchen-- which itself is undergoing massive change and dislocation. Don't hold your breath.

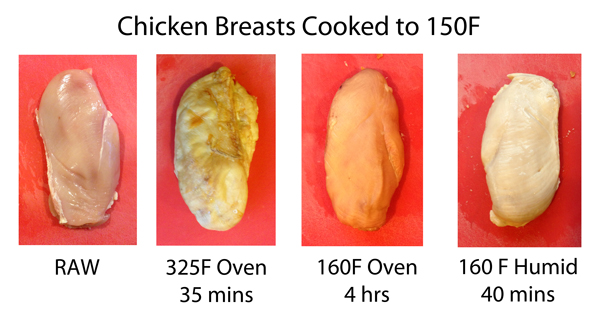

Yet it's possibilities are tantalizingly, and can teach us much about the physics of humidity. In this first simple experiment, I compared the results of cooking a chicken breast three ways- in a hot, conventional oven, in a low temperature conventional toaster oven, and finally in a low temperature combi-oven. The breasts all weighed a half pound (275 gms), and were pre-salted with about 1/4 tsp of sea salt. Each breast was placed on a rack held 1.5" above a drip tray and cooked until their centers reached 150F. The first chicken was baked at 325F- just the point where the Maillard reaction starts browning flesh. The other two were cooked in ovens nearer to their final resting temperature- around 160F. Low and slow. The only breast exhibiting any darkening was in the high temperature oven.

The 325F oven-baked chicken breast was moist, with a slightly dried surface. The 160F oven encased the breast in a tough "pellicle"- it was on its way to becoming chicken jerky- but the center was still tender. The combi-oven breast was as pale as a ghost, but it was also the moistest of the three and lacked any hint of a dense, plastic-like surface skin. (If you miss that crunchy brown flavor, you might cook the breasts to 140F, then remove and sear on a grill. But our interest here is their relative texture). This was reflected by the weight loss:

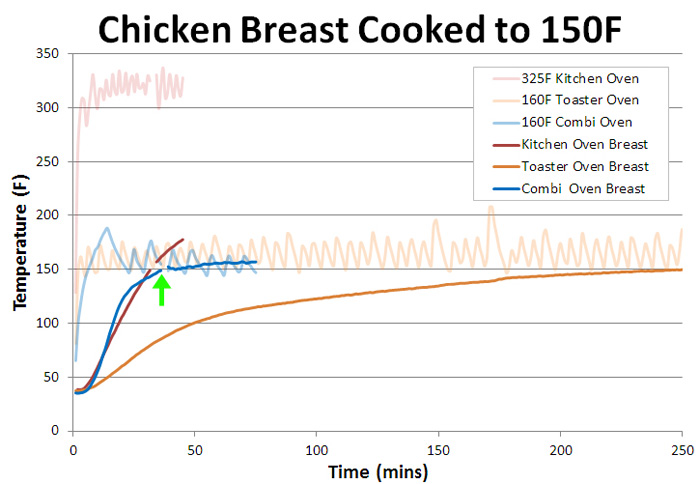

In addition to moistness, there was a major differences in cooking time. The 325F and combi-oven both took about 35-40 minutes to reach done (green arrow below). Which is amazing, since the combi-oven was idling at 160F! On the other hand, a 160F dry toaster-oven took nearly 4 hours to finish cooking. Why so different?

There are two reasons. First, in the dry 160F oven, the breast evaporatively cooled, and this cooling slowed the temperature rise significantly. Just as sweating delays heat exhaustion in a runner. Without evaporation, the breast would reach 150F in 120 minutes; with evaporation, 240 minutes. Secondly, in the combi-oven evaporative cooling was overwhelmed by the "latent heat of condensation" from the surrounding humid air. Everyone knows sweating doesn't cool you off on a humid day, because water vapor re-hydrates your skin as fast as it evaporates. No net gain. So evaporative cooling is mitigated in a humid oven. More critically, when water molecules in the combi-oven touch the cold meat, they condense. And this condensation liberates a significant amount of heat. Imagine water molecules as those little magnetic marbles, "heated" (i.e. shaken) to the point where their rapid motion keeps them from ever sticking together. But when they encounter a cool surface, they slow down and link together with a "clunk". That clunk of condensation represents an extra, *latent* energy released to heat food. As the breast warms and draws closer to the oven temperature, the effectiveness of condensation drops, and so the cooking rate slows. But, as it slows, water molecules leaving the meat- and thus drying it out- are replaced almost immediately by humid air. Assuring hot meat is both tender and juicy. By cooking near the final temp- e.g. 160F for a 150F chicken breast, the chance of overcooking the meat is greatly reduced. Here, I returned the breasts to the oven for an extra 10 minutes- as you can see, if you forgot to pull dinner from a 325F oven because the doorbell rang or Facebook called, the result is instant shoe leather. Forgetting is not very forgiving. But the combi-oven produces great results 10 minutes, or even 60 minutes, later.

So the combi-oven

Will the combi-oven ever be as popular as the microwave oven? Probably not- too complicated, and frankly, today most consumers are cooking voyeurs, travelling in a land of take-out and television. But for those who care about their food, a combi could be the one oven they will ever need.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 The Cuisinart would benefit from accurate humidity control (though measuring humidity at high temperatures inexpensively is a challenge). And better control over air-exchanges. On regular toast or broil settings, the oven is so well sealed the trapped humidity interferes with browning. So its hard to steam and then brown. 2 In barbecue, cooks often wrap their meat in foil part way through smoking (the "Texas Crutch") to prevent drying. Few smokers are able to control humidity, except indirectly by mopping the meat, closing the dampers, or filling the smoker with a few hundred pounds of moist pork shoulder...

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |