| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| cool it | |||

|

April 2018 |

|||

|

Summer's coming. The great outdoors. The beach. And salmonella. Packing snacks in the morning and keeping them cold all day long seems like a breeze. Just pick up one of those inexpensive reusable insulated lunch bags, slide in a packet of ice, and you're good to go.

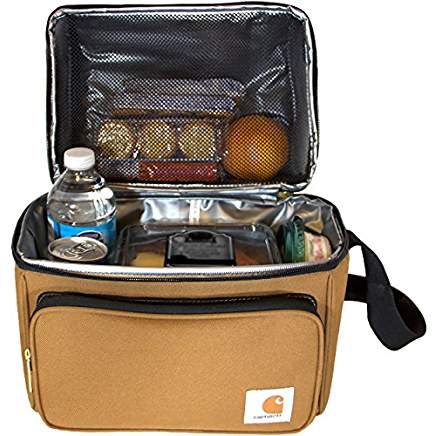

But how effective are these bags, really? And will the slabs of blue ice or sealed mylar packets make it through the day? Keeping your food, and family, safe? So we ran a few tests: One of the most popular styles of insulated bags is shown above in gray. Around 2.5" thick and the dimensions of a sheet of paper. The interior is lined with a reflective foil, surrounded by 1/4" thick walls of insulation.

When you drop ice cubes into a glass of lemonade, they don't immediately melt. Instead they linger on for an hour, slowly dissolving into the drink. The reason is a phenomena called "latent" heat phase change. As heat enters the ice from the warm lemonade, the ice molecules begin to vibrate with increasing intensity. Despite this thermal urgency, they are still unable to break the ice molecules apart. But once enough heat is absorbed, the ice suddenly melts. Polymer ice behaves in the same manner, but melts at a temperature lower than water ice. Here, we filled two plastic one-pint deli containers with 12 oz of water or polymer, froze a thermocouple in the center of each container, and left it on a counter-top to melt:

As you can tell, for around seven hours the polymer ice is colder is colder than water ice, then abruptly melts, The water ice melts an hour later, but was 5-10F warmer during most of the test. So, the claim that polymer ice might be a more effective way to cool a lunch bag has some merit. But how will the ice pouch function in a more complex, real-world environment? For this initial baseline test we placed a single packet of water ice into the gray lunch bag, along with two soft drinks and a sandwich. In most cases, the ice pack will drop to the bottom of these tall bags. As the bag fills with food, the ability of air to convect and mix hot and cold regions diminishes. Effectively isolating the top and bottom of the cooler. So the temperature was measured at two locations, e.g. the bottom quarter and top half of the bag (which remained vertical at all times):

The bag sat on the kitchen counter-top as the house heating system turned on and off (the spiky top curve), which then caused the bag's interior to rise and fall in synchrony. And what is the target temperature against which we measure success? Well, the USDA advises keeping perishable food that might carry salmonella or e-coli below 40F. We chose 45F as our criteria, as the USDA is (rightfully) conservative. Clearly the water ice did a pretty good job at the bottom of the bag, staying below 45F for around 5 hours. But, the top of the bag was ALWAYS in the danger zone. Hot air rises, cold sinks, and air is an excellent insulator. So the cold ice pack wasn't capable of cooling the top of the bag.

This interior gradient is also telegraphed by the bag's external surface temperature. As this infra-red image illustrates, the bag's top is 5-10F warmer than the bottom:

Can the polymer ice do any better? Well, the top of bag is still isolated by air insulation, and the sandwich is blocking air flow. But in the bottom of the bag, the polymer ice kept the food slightly cooler than water ice, at least for the initial six hours:

Unfortunately, on a hot summer day in a simple insulated lunch bag, even polymer ice is not up to the challenge. It only provides about an hour and a half of microbial protection (and only 30 minutes at the USDA standard of 40F):

A tightly packed lunch bag would perform even worse. Clearly unsafe! So what precautions must a concerned parent take when sending their kid off with ham sandwich on a hot summer day?

|

|||

|

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- You can fabricate your own polymer ice bag by grabbing a super-absorbent diaper and cutting out the white absorbing layer. Place in a thick zip-locking bag, add water until it won't absorb any more, and zip closed. I tested Huggie's polymer absorbing 10oz of water, and it freezes at 30F (rather than 32F pure water). Not only is the freezing point a bit lower, but the pouch can't leak if punctured.

We also simulated the thermal performance of the bag in Solidworks, including convection. In an empty bag, placing the ice at the top of bag allows cold air to drop to the bottom, rewarm, and then rise upward to be chilled by the ice. The resulting circulation pattern looks something like this (arrow color denotes temperature):

When the pack is placed on the bottom, the cold air simply pools in place.

In a real lunch bag, circulation is impeded by food and drink. The air is basically stagnant. So the actual gradient is more like the image below. Of course a fan or heat pipe could improve mixing. But an even better solution is a pack of ice that covers all six walls, so heat has to pass through ice to reach the food.

|

|||

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |

For the ice, we chose the mylar-bag pouch made by

For the ice, we chose the mylar-bag pouch made by