| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| mind the gap | |

|

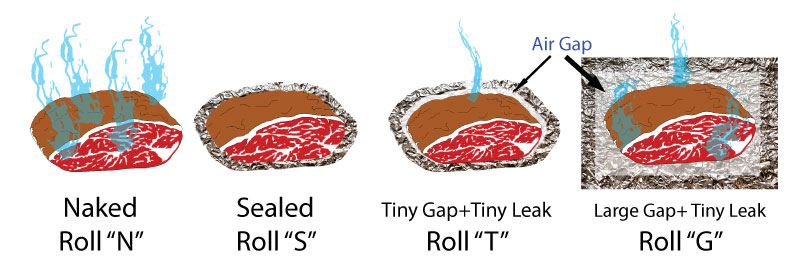

Sept. 2013 The first time man roasted meat over fire, the carcass was probably wrapped and steamed. Not in banana leaves for pork lau lau, or corn husks for chicken tamales. But steaming in its own natural hide. Meat is ⅔rds water. When you cook skinless meat over an open fire, browning and polymerization contribute aroma and texture directly onto the meat's surface. Those flavor molecules which can't evaporate, concentrate with time. But without a skin barrier, water is also constantly evaporating, increasing the risk of drying out and potentially turning dinner into jerky. Alternatively, steaming preserves moisture, and, by accelerating the breakdown of tough collagen into slippery gelatin, tenderizes meat faster than it can dry out. But steam and braising liquids also draw out flavor from the meat into the jus, and its texture may slide from tenderness into mushiness in a matter of minutes. So how do we balance flavor and tenderness, speed and consistency? In the world of BBQ, many people split the difference. They start by smoking raw, skinless meat uncovered. This step builds color, smoke flavor, and a crust. Then, part way though the cook (and exactly when is a state secret), they wrap the meat in foil or butcher paper. Which is often called the Texas Crutch. This step speeds up cooking and steams meat into tenderness. So when should you wrap? And how should you wrap? And what can go wrong? The Texas Crutch is closely related to braising in a Dutch oven, especially if you douse the meat with large quantities of sauce or injected marinades before sealing in foil- see this article for details. The Texas Crutch is a milder form of braising. Just to make the science easier to explain and interpret, let's start with a simple model system. Instead of meat, with its complex array of fragile proteins, fat, collagen and juices, we constructed a tightly rolled cylinder of cotton fabric dipped in water. About 2.5" in diameter. This faux roast absorbed about 70% water by weight (500 gms)- just the same proportions as in meat. Four identical cylinders were assembled, each wrapped around a thermocouple.

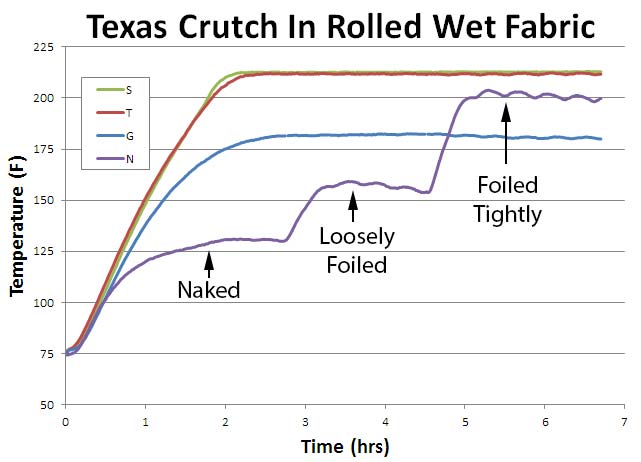

These four examples cover a wide range of Texas Crutch foil envelopes observed in backyards and at competitions. Some people take the time to triple fold the seams, double wrap and compress the foil against the meat (Roll S). Others just cover with foil, and hurriedly crimp the edges together, leaving a square inch or more of aggregate vent area from all the mismatched edges (Roll T). And finally, some people place their partly cooked meat in an aluminum tray, tent the top and crimp the edges together, but leave a thick air cushion between the smoker's heat and the meat (Roll G). It is hard to prevent air leakage in a tray or a lightly crimped foil pack. Imagine there is a 1/32" gap around the perimeter of a 12" tray or sheet of foil- this can add up to almost a one square inch leak! Recall that evaporative cooling and the stall results from the interplay of three variables. First, evaporating moisture carries away heat and cools off the remaining mass. The same reason sweating cools you off after a long run. Second, at higher temperatures the rate of evaporation, and thus its cooling power, increases. That is, water evaporates faster on hot days. And thirdly, energy absrobed from the hot air is basically constant over time. So, as any moist objects heats up, the evaporation rate (and thus cooling rate) rises until it matches the heat input from the oven. And then it stabilizes, maintaining the same temperature forever if nothing changes (of course, the meat will eventually dry out, and the temperature will begin to climb again). All four samples were placed in a 225F convection oven -- the moving air simulating combustion currents in a smoker. In the first hour or so, the tightly sealed and compressed sample "S" heated up the fastest. The foil prevented evaporation so it stopped cooling in its tracks. Just like a raincoat will cause a sweaty runner to overheat. The naked roll "N" evaporatively cooled over its very large surface area, and rose most slowly in temperature. The sample with a large air gap (Roll G) loweres moisture evaporation because the container is sealed, but air is an excellent insulator, so it also limited the heating rate from the oven. Consequently, despite a relatively small air leak, there was sufficient evaporation to cool the foil envelope and stall at 180F. Roll T with a tiny gap potentially could evaporatively cool, but the foil was so tightly compressed against the fabric, that little moist air could escape through the tiny blocked vent. After one and a half hours, the naked roll stalled at 135F.

After 3 hours, I covered the naked roll with foil- just as if you were smoking brisket the Texas Crutch Way. But, I left about ¼ to ½ inch of insulating air between the foil and the roll, plus didn't tightly seam the foil. A pretty common situation with many cooks, rushing to put the meat back on the fire. While the the loosely wrapped foil does slow evaporation, as the temperature rose, the cooling rate increased, and eventually a second stall occurred at 155F. At 4.5 hours, I tightly pressed the foil against Roll "N". This blocked evaporation over most of the surface and the temperature rose, until it stalled a third time, at 200F. So, when foil wrapping, attention to detail makes a HUGE difference in determining how quickly meat cooks, how often it stalls, and the ultimate temperature it reaches. With this simple experiment complete, let's try cooking beef brisket points and pork shoulders. The real world is similar to our idealized experiments, but more devious ....

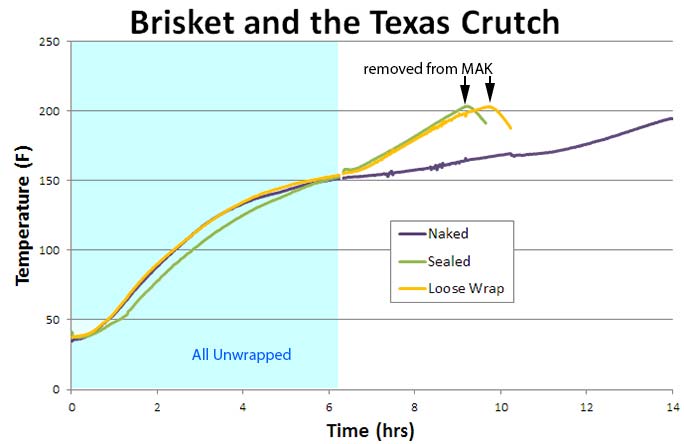

I cooked three brisket points1 (6 lbs each) in a MAK pellet smoker at 225F. All three were smoked until their internal temperatures reached 150F. One naked, one sealed tightly in foil with no gaps, and one more loosely wrapped. The foiled briskets were cooked until they reached 203F. They were then removed from the MAK and continued to cook off their own stored-heat for an hour in an insulated box. The third brisket sweated naked in the smoke until it reached 195F.

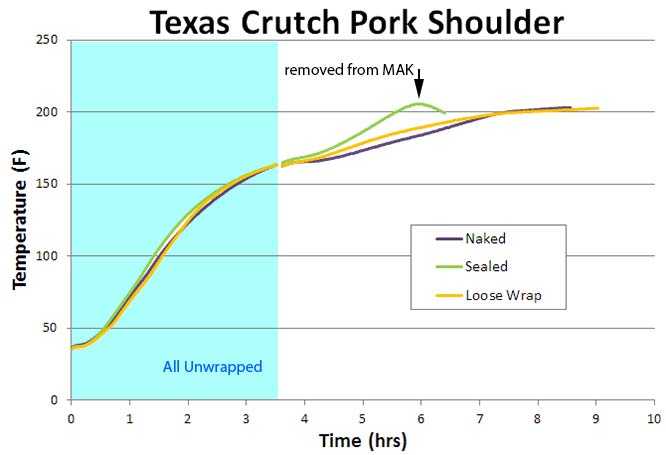

Note how the foiled briskets cooked much faster than unwrapped- almost 4 hours faster. While there was only a small time difference between the sealed and more loosely wrapped points. Why? Well, unlike moist rolled fabric, meat exudes juices. Each packet retained almost 12 oz of exuded liquid, and these juices filled in the air gaps of the more loosely wrapped crutch, increasing the thermal link to the hot smoker. So, in reality both became tightly wrapped. In terms of doneness, all three points were tender. Although I removed the naked point from the smoker at 195F (instead of 203F), it had more time for collagen to break down, so tenderized at a lower temp. One reason not to take end-point temperature recipes at face-value. We then performed a similar experiment on three, 4 lb pork shoulders in a 225F convection oven. Again, the tightly wrapped shoulder (Green) cooked faster than naked (Purple), but the loosely wrapped (Gold) behaved more like the naked. Why?

Pork shoulders produce less juice than briskets and tend to dry out earlier in the cook while still naked. So, even loosely wrapped, the small air leaks were large enough to let the little evaporative moisture escape- almost cooling as efficiently (given the slight insulating value of the foil air gap) as buck naked. From a texture perspective, the tightly sealed pork was perfectly cooked when it hit 203F. The naked and the average wrap were slightly mushy. Which is why you should always be skeptical of recipes which adamantly insist on hitting a particular temperature to achieve "done". Done depends on total history, including oven humidity, time of wrapping, the meat's original moisture content, etc. For this reason, sometimes it feel like all hell has broken loose in your back yard:

If you Texas Crutch by placing your meat in an aluminum tray covered with foil, cooking speed is slower than when wrapping tightly in foil. Because stagnant air is an insulator and slows the influx of heat. Even a tiny air leak/vent will release some moisture, and since the rate of heat influx is lower in a tray, much less evaporation is needed to cool, and the meat stalls again. Some people tent with plastic wrap under the foil to block the smallest gap- this works, but plastic wrap IS NOT SAFE ABOVE BOILING TEMPS3. So what have we learned?

If you are stalling in the crutch, and prefer to speed things up, try:

|

|

|

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 You may have noticed the green line brisket cooked slower than the other two, at least until foiled. At the market I could feel the texture of each muscle group through the cryopac, and this point was distinctly softer and wetter than the other two. Which is why it took longer to cook, but eventually caught up and started to stall around the same time. Still, this explains why some days meat takes 11 hours to cook, and on other days, 13. 2 Even though Roll T has a tiny vent on the top of the foil, it was so tightly sealed, little moisture evaporated. But some moisture escaped. The way you can tell are the small wiggles in the 212F stall for Roll T that are absent in Roll S, which was as close to perfectly sealed as practical. The wiggles reflect the oven cycling on and off between 200F and 250F to hold the average 225F temperature. As the oven cycled, evaporation followed in sync, causing the temperature to vary. 3 From the Saran website:

|

|

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |