| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| nap time | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

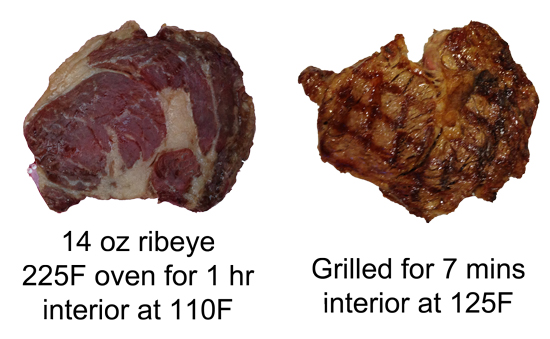

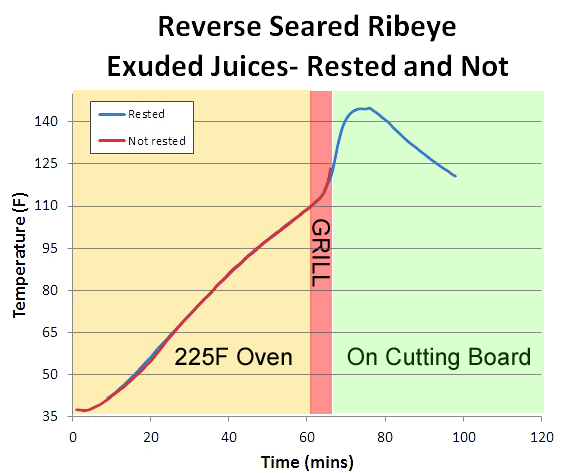

Jan. 2013 A mid-day rest is said to relax the mind, allowing one to absorb new concepts and more easily retain memories. But is resting as important for meat, as it is for your mind? According to conventional wisdom, after grilling a steak or baking a roast, we are sternly admonished to "let it rest" under a foil tent. Supposedly, this five, or ten, or twenty minute "nap" allows the meat to reabsorb juices that might otherwise ooze out and be wasted. Certainly, the cutting board is often a "bloody1 mess" after slicing- wouldn't it be nice if a simple "time-out" was the solution? But how much liquid actually oozes out, and why? Even a review of the scientific literature reveals there is no broad consensus on the details. Unlike a rose, a meat is not a meat is not a meat. The moisture's fate depends on the breed, the feed, how it was slaughtered, whether the meat was frozen or injected or mechanically tenderized, aging, salting, the fat cap, and on and on. The hallmark of science is reproducibility, but in food science, mere concordance in closer to the norm. Surprisingly, most meat is around 70% water. Some of this moisture is in the form of water chemically and mechanically stored between the cells (myowater). Some of the moisture is in the form of myoglobin stored within the cells, while still other water molecules are embedded deep within complex proteins and polymers. And juice is only one measure of a perfect "bite". Tenderness, which is more a consequence of marbling, enzymatic dissection of muscle proteins, and gelatinizing collagen depends only slightly on juice content2. Some people enjoy the flavor of a hot steak, particularly the crispy bark that sogs out if rested. Others prefer the softer, more relaxed texture of slightly rested meat. But juice is the surrogate that is most visible on the plate, and the one that invites the most controversy. No one said this would be easy. Myoglobin is mostly stored within the cells, and not released until the cell walls start to break down (although a bit oozes into the the intercellular spaces, to join with the myowater that is loosely bound). But even the concept of "loosely bound juices" is a convenience. There are a continuum of forces holding water molecules inside meat- some weak enough to be dislodge with gentle thumb pressure, others requiring the heat of cooking, and still others, near charring flames. Then there are the massive changes induced with temperature. The first "sweat" occurs with very loosely contained water oozing out through relatively wide channels in the meat. As the heat increases, more tightly bound water is freed, but this water must diffuse from the meat's center to the surface to evaporate, which takes time. Then, around 135-145F, the collagen web which holds the muscle fibers together begins to shrink before finally softening into gelatin. This "collagen corset" squeezes on the muscle fibers, wringing out additional liquid- some myowater, some myoglobin from burst cells. Which is why a temperature probe inserted in this range appears to have struck an artesian well. In a thick roast cooked at high temperatures, the top 1/8" of the roast might reach 200F or higher and almost desiccate, while the interior is still raw. Yet a St. Louis rib cooked low and slow might be at the same temperature from bark to bone. So the moisture profile is grossly non-uniform. At higher temps still, more cells break, enzymes complete their digestion of proteins, and more myoglobin mixes in. Some of these processes are irreversible (e.g. burst cells walls, or denaturing of proteins), while others allow for a bit of re-adsorption as the meat cools (e.g. surface tension and capillary sponge effects). But in general, when the juices are freed, they remain at large. A good analogy is to imagine a pile of coals soaked with gasoline. When you first light the coals, the surface gasoline burns (e.g. the drip and loose myowater easily emerges). As the temperature rises, gasoline absorbed by the coals diffuse out of the coal "sponge" and burns, but the coals stubbornly refuse to ignite. Finally, the coals themselves begin to crack open, dry out, burn and release their own heat. Burning the moisture out of meat is nearly as complex as the mastery of fire. So let's get started. As a first test, we grilled two 13 oz (395 gm) rib eyes, each 1½" thick. The best way to cook a steak is to limit the time spent over the highest heat. While its true a roaring flame produces a brown and flavorful crust, the high temperatures also overcook the outermost steak layer while waiting for the inside temperature to catch up with the surface. Resulting in a thick gray band surrounding a pink center. So, chefs are increasingly turning to a two-step cooking process. One step holds the meat at a low temp (225F in this case), for the temperatures to equilibrate throughout. The second high-temperature step produces the crust. We chose to warm the meat first and finish on the grill- the so-called "reverse sear"3. After salting the meat (¼ tsp/lb), each steak was placed in a low (225F) oven. Because they were so thick, it took almost an hour for the inserted thermocouple to reach 110F. After an hour's warming, the meat lost around 10-15 gms of weight- almost exclusively in evaporated moisture. You can see how the steak darkened a bit and the surface dried off during this first pre-cooking step. Then, I seared the steak on a very hot gas grill4- it took just 7-8 minutes to brown the meat and for the interior to reach 125F (a nice rare).

The high temperature searing also extracted moisture-

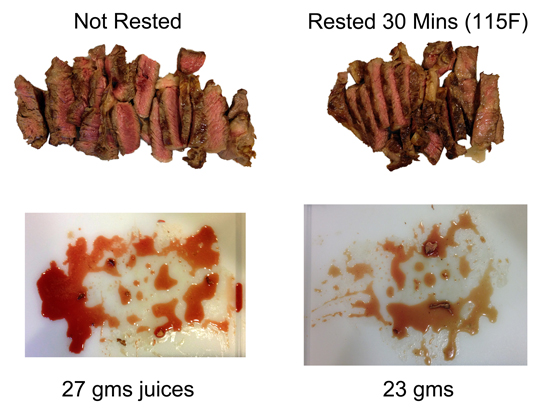

I immediately sliced the steak into narrow strips. This quickly cooled the meat, locking in the rare color and exuding a deep-red, low viscosity juice. Since people almost never devour a 13 oz steak in seconds (plus it takes time to set and serve at the table), I measured the amount of juices exuded five minutes after slicing- by sopping up the liquid with a paper towel, and gently patting off the ¼" meat slices. This is the "Not Rested" experiment. By comparison, I left the "Rested" steak sit on the cutting board until the internal temperature dropped to 115F. Five minutes into the resting period (but before slicing) some light brown juices emerged. Around 9 gms. Because of "carry over" (that is, the very hot surface crust continuing to heat and cook the interior even when off the grill), the temperature rose to 143F during the resting period. After 30 minutes resting (it was, after all, a thick steak), the meat finally dropped to 115F. I then sliced the steak, waited two minutes for any juices to appear, and lightly patted the board and slices dry with a paper towel. These juices were a bit thicker than seen with the unrested meat, and tended to adhere to the outside of each slice.

You can see the difference in color between the rested and not-rested meats and their juices- the additional carry-over cooking time converted a rare cut to medium/rare.

You might expect resting to "absorb" juices back into the meat, although the data says otherwise6. Unrested, the juices flow out almost immediately. Rested, only after slicing do most of the juices emerge. It appears the cut surface releases juices from about 1/4" back into the muscle:

Within experimental variations (and consistent in two repeated tests), a dead-heat. In a thinner steak, there is absolutely no difference between resting and eating the steak roaring hot. But what about in a thicker roast? And one cooked at higher temperatures, where collagen shrinkage might play a role? In a series of tests I measured the juice loss in 1 kg (2.2 lb, 6"x4"x3") pork loins, roasted in a 400F kitchen oven5. These cuts have very little fat and are very uniform in cross-section, so any weight loss is due to moisture loss. As before, the meat was salted for a few hours before roasting, with 1/3 tsp sea-salt/lb. The first thing you notice (not too surprisingly), is the longer you cook meat, the drier it becomes. These temperatures are measured in the center of the roast immediately after cooking- they rise 5F higher after resting7.

A clear reason to eat roasts and steaks rare or medium rare... Around 135F, moisture loss accelerates as the collagen shrinks. This effect is particularly visible if you carefully measure the exuded juices. After cooking two roasts to 125F, slicing one 3 minutes after cooking, and letting the other rest for 25 minutes before dividing in 3/8" slabs, we see very little difference in the final results:

I then repeated the same experiment at 140F:

Now we detect a real difference between resting and not resting- about a third more juices are squeezed out by the collagen shrinkage at higher temps. Which is significant, except some of these juices are easily reabsorbed if you don't strand them on the cutting board. I took all 91 gms of not-rested juices, drizzled them over the meat, waited five minutes, then re-measured the amount of juices on the cutting board. Around 62 gms. About the same as resting. In other words, some of the exuded juices arose from irreversible changes in the meat structure or irreversible chemical reactions. These are lost to the roast, whether rested or not. Other juice fractions were held in by capillary action and weak bonds- these can be reabsorbed. And here's an interesting side note- the resting meat is also steaming hot, evaporating moisture quickly at first and more slowly as it cools off. In addition to the 64 gms of exuded juices, the meat evaporated an additional 13 gms into the open air, and nearly 20 gms when tented, over the 20 minute rest period. This is moisture the not-rested loin retains, because slicing cools the meat so rapidly. So its a tie. Besides, in the real world meat is always consumed somewhere between these two extremes. Its takes (or should take, if you remember to chew each bite 10 times like your mom taught) a half-hour to eat a steak, which means the last bite is fully rested, even if you started slicing the first off on the grill. The more important task to is utilize these juices, no matter when they appear. For the non-rested meat, you can always create a "board dressing", simply by adding some chopped herbs, butter, and even a reduced sauce to the board juices, toss the dressing over the slices, and serve. Amazing flavor. Or, if you rest the steak before eating, serve each person an individual portion and let them carve so the juices emerge on the dinner plate or adhere to the meat. Just make sure your guest can sop up the liquids with bread or rice. Finally, if you "cut" large hunks of meat out with your teeth7, let the juices leak into your mouth. Mix with beer and enjoy. Not salting meat a half hour before grilling is a crime against nature- it adds flavor and nearly doubles the retained juices. Not resting the meat before slicing is a choice that barely affects the tenderness or juiciness of your meal- feel free to be creative. In summary-

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 The juices are not actually blood- which drains from the animal after butchering- but myoglobin. Blood contains hemoglobin which carries oxygen from the lungs to the cells. Myoglobin then accepts this gift of oxygen and stores it as fuel within the cell. What emerges as "juice" during cooking is myoglobin, along with water, fats, proteins and dozens of other chemicals. 2 Tenderness is a much more nuanced concept, and only distantly related to juiciness. A 2011 review article by Pearce et al in Meat Science illustrates the complexity of this subject. 3 The "reverse sear" technique is probably quite old, but gained traction in commercial kitchens in the late 1980's. Called either "par cooking" or "staging", restaurants needed a way to partially cook food in preparation for the evening rush. For a while, industrial food suppliers offered fully cooked fish, steak, veggies etc. sealed in vacuum bags from their catalogs. Ready to simmer in water, cut open and serve. Up to, and including "grill marks" sometime painted on the meat with brown ink! By the 90's, chefs recognized the advantages of humid pre-cooking, but for reasons of flavor and freshness started to finish the par-cooked food on the grill or in the pot. Thanks to food bloggers and TV, this method has moved out of the professional kitchen into the home. Today, your hamburger's juicy pink interior may have the reverse sear to thank- whether at home, or at a restaurant. 4 Normally I grill and lightly char steaks over a blazingly hot lump coal fire, but it's hard to reproducibly control the temperature with an open flame, so for these experiments I switched to a gas grill. But the reverse-seared dry steak surface helps the meat brown instead of steam- whether cooked on a hot grill, or merely a warm grate. 5 I chose pork loin to emulate Cook's Illustrated's related experiments from their "Science of Good Cooking" book. Commercial pork loin is lean and contains modest amounts of collagen- cook a loin beyond pink (135F) and it's tough going. So I never roast loin that high. But for consistency we tried 140F. The Cook's Illustrated experiments at 140F also demonstrated even greater juice losses without resting. But they did not salt, they sliced more thickly so fewer juices would leak out, did not take into account juices clinging to the slices, and did not check if a board sauce would be reabsorbed. So I do not consider their results to support the "resting" hypothesis. 6 Looks can be deceiving. Humans tend to misestimate volumes based on area, so a thin layer of juice on a large cutting board *seems* as if the meat has drained itself dry. Here is a photo of a 1/2" thick by 3/4" bite of pork loin, next to the amount of juices this single bite would have exuded on the cutting board after resting and slicing. Your tongue probably notices as this small amount of juice as it lubricates a bite, but it's not at all clear a little more or less makes a difference. Especially if that difference is part of a surface glaze or gravy. On the other hand, while meat originally contains 70% moisture post-butchering, some of that moisture was lost during storage (drip loss), and some moisture is so tightly chemically bound it does not add to the mouth feel. Let's say the "juice" content of meat is closer to 60%, or 600 gms in the case of a 1 kg roast loin of pork. At 400F, cooking and slicing removes another 300 -350 gms. And the most mobile juices left earliest, so the last 10 gms of juice may disproportionately affect mouth feel. But our own experiments, along with many in the literature, demonstrate if the meat is not overcooked, 20% changes in the juice levels are not really detectable.

7 An astute reader may have noticed the pork roast carried over by 5F, while the steak by 15F. The reason is surface to volume ratio. For example, imagine the hot surface layer that continues to heat the meat off the fire is 1/4" thick. In the steak, the heat in this layer only has to migrate a 1/2" from each side to reach the middle. And the 1/4" layer is 33% of the total volume of the steak. But in the 3"-4" diameter roast, the heat has to travel 1.5" to reach the center. And, the 1/4" surface layer only encompasses 20% of the volume, diluting its heat energy over a larger mass. So its no surprise the carry over is greater in a steak than a roast,... This raises a small but important issue. If you compare the rested to the not-rested meat, when both are pulled from the oven at the same temp, the rested meat will be hotter before slicing due to carry over. Not too significant if the carry-over remains below 135-140F (where collagen shrinks), but it might affect the difference in say a thick medium rare steak that carries over to well-done. So in the pork tests I actually removed the rested meat from the oven a few degrees before the non-rested, to partially blunt this effect. 8Of course, if you gobble up 2" cubes of meat, few juices will emerge on the plate. Just make sure your guests know the Heimlich Maneuver. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||