| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| a salty tale |

| March 2016 |

|

Salt is a widely used preservative, quickly drying out microbes and disrupting cell membranes. So, it is a matter of "common sense" to limit direct contact between yeast and salt when kneading dough. Or chance interfering with the rising process. On the other hand, yeast -- a hardy, ubiquitous microbe, might simply shrug off a bit of NaCl. And many successful recipes mix salt and yeast into the wet ingredients with abandon. Does the truth lie somewhere in-between? The answer is revealed by two experiments. First, we check if yeast-growth is inhibited by salt in a "petri dish", and secondly, if it makes a difference in an actual bread recipe. Instead of petri dish, we chose a plastic bottle, and dissolved yeast in warm water mixed with a meal of sugar (see footnote below1). To see if the yeast was damaged, we measured how much CO2 the yeast exhaled. And it turns out the yeast is just fine, breathing out the same amount of CO2 whether floating in plain sugar water, or drowning in water tainted by 1.5% (or even 5%) table salt! Common sense 0, Science 1. Secondly, we compared four traditional, but different strategies for incorporating salt. These are:

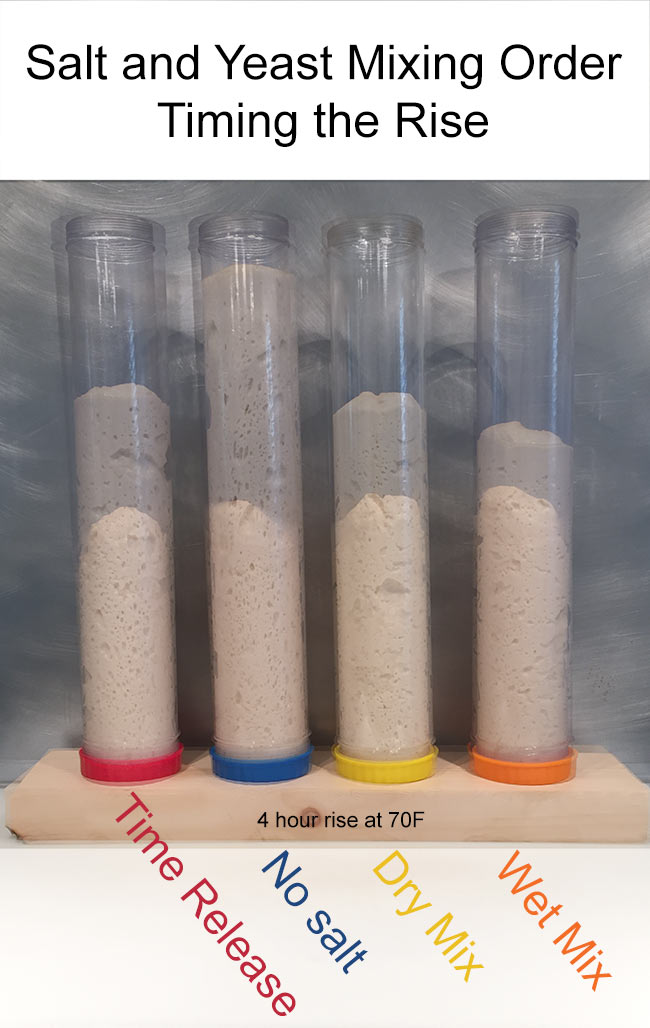

Salt helps strengthen the gluten matrix, ensuring trapped CO2 bubbles are more stable. The WET MIX guarantees all of the starch and gluten proteins are uniformly coated with their share of salt ions. Not too high a concentration to damage the protein molecules, but enough to hold onto water and build additional structure. However, this method gambles with killing the yeast floating in the salty wet mix. At least that is the theory. The DRY MIX and TIME RELEASE technique initially keeps the salt localized, until moisture slowly dissolves the salt grains and the ions diffuse into the dough. Theoretically, this might give the yeast a head start reproducing in a salt-free environment. On the negative side, locally high salt levels might create pockets of non-uniformity where CO2 bubbles can easily break through. Plus, the enormously high salt concentrations adjacent to the grains can actually damage the gluten structure2. We prepared samples by all four methods, and to visually monitor the dough's rise, inserted a log of dough into 2 1/2" diameter clear oiled tubes. Some experiments used warm water, other room temperature water to assure thermal uniformity. Some with dry active yeast, others with cake yeast. While the rise times varied, the results did not. The bread recipe is adapted from a standard "no-knead" dough:

Here is a typical result- in this case, for room temperature (68F) water and dry active yeast. The image is a double exposure take at the beginning and the end of the experiment:

At first, it looks like NO SALT recipe is the most yeast friendly. After all, it rose the highest. But this has nothing to do with the yeast, which laughs off salt. Rather, the lack of salt means the dough is softer and more easily inflated. Like blowing up a party balloon vs a car tire. And, the lack of salt means less water chemically bonded to the starch, so the dough is wetter. Consequently, this dough, when re-kneaded, deflated the most. And when baked, slumped and formed a flat boule. The WET MIX dough rose slightly less than the other two methods. Again, not because the yeast was damaged, but because the gluten network is strongest. This dough baked into a nearly round boule with large air pockets and visible sheets of gluten spanning the pockets. Finally, as expected, the two salt grain methods rose to exactly the same height. With well shaped boules, and decent structure. In other words, you can add salt to a bread recipe whenever you prefer. I prefer the wet method- it is more uniform and reproducible. Plus, in a quick bread where there isn't time for the salt crystals to melt and diffuse, the dough's structure is more highly developed. But this is one case where common sense fails.

|

|

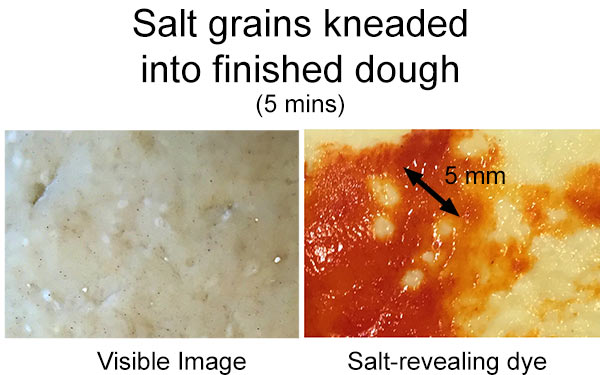

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 We looked for any possible salt suppression of yeast growth by mixing one package of dry active yeast into one liter of warm water, then stirring in 1 tbs of sugar to feed the yeast. And shook the bottle every 15 minutes. We also tried cake yeast with similar results. Salt levels were varied from none, to 1.5% (typical of many bread recipes) to 5% (extremely salty). Yeast activity was measured by CO2 gas emission. In some experiments gas was trapped in a sealed bottle and vented through a bubbler- the bubble rates for all three salt levels were the identical. We also captured CO2 in a condom, and again the rates were the same. We also compared regular to iodized salt. In high concentrations, iodine is a potent disinfectant. In low concentrations, an essential nutrient blended into table salt to prevent diseases such as enlarged thyroid or neonatal cretinism. The level in table salt is a mere 45 parts per million, and iodine compounds (such as calcium iodide) are often mixed into commercial bread doughs as a conditioner. So you won't be surprised to hear that in our tests that yeast and iodized salt grew just slight FASTER than plain salt. In other word, trace amounts of iodine will not harm yeast. A photo of the condom CO2 collection balloons will appear when you mouse-over this colored triangle. 2 It is very challenging to uniformly mix salt grains into bread dough. Just try blending a drop of food coloring into partially kneaded dough- even after a few minutes, streaks of dye remain. TIME RELEASED salt often segregates into bands as the dough is folded and kneaded. In the first hour or two, the salt is visible to the naked eye as patches of raised, lighter "goose bumps". Over time (and this can mean a few hours), the salt dissolves and the white spots spread out and join together. Remember, most of the water is tied up by the starch and protein molecules, very little is "free" to melt the salt. So, it could take days for salt granules to become as uniformly distributed as salt brine in the wet method.

Table salt crystals are about 0.3mm cubes. Combined with the density of salt, a 1.5% concentration would average a grain spacing in the dough of around 4 mm, with a large variation based on the kneading pattern. The salt dyes are described here- basically, the dye turns white where the salt concentrations are high, and red, where low. Photographed in a bagel dough, which is relatively dense at around 35% water by weight.

|

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |