| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| foggy ideas about smoke | ||

|

||

|

October 2011, May 2014 Summary of how smoke is deposited on meat:

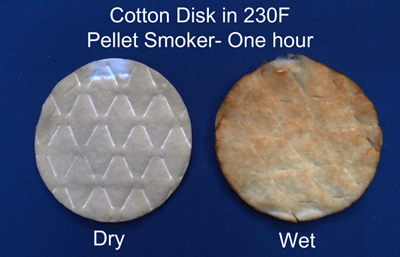

Ever take a walk through a dense fog, only to emerge perfectly dry? While a stroll in the gentlest rain soaks you to the bone? Well, a similar phenomena happens in a smoker, leaving flavor to essentially go up in smoke... There are many reasons most smoke particles never lay a hand on a pork shoulder. When wood is burned, some of the combustion products are gases (like carbon monoxide and methanol), some are polymers like creosote and phenols, and some are ash. And much of it is eye-stinging, cough producing smoke. All of these combustion products contribute to the flavor profile, and only a few are responsible for the infamous smoke ring, but none of this matters if these chemicals are never absorbed by the meat in the first place. Even after hours resting in a fog of smoke. Curiously, around every object is a stagnant halo of air called the "boundary layer". Think about a crowd leaving a concert- the people near the wall can hardly move, while those in the middle flow out through the exit. A similar viscous layer of air builds up around any impermeable surface. Depending on wind conditions, surface roughness, etc the stagnant layer of air around a piece of meat might be a a few millimeters to a cm or more in thickness. When smoke particles or other combustion products flow from the fire to the meat, they may or may not actually intercept the meat's surface. Small particles and entrained gases, in particular, are carried along with the flow, while inertia allows heavier, fast moving particles to impinge on the surface. Just like tiny fog particles flow around your body, while small rain drops pelt your skin. We've all cursed this piece of physics while driving- gnats follow the air-stream over the windshields, while larger insects leave green sticky splats at the point of impact. Although smoke particles are too small to see with the naked eye, the smoke's color provides a rough dimensional guide. Pale blue smoke particles are the smallest- under a micron, and around the size of the wavelength of light. Though a mechanism called the "Tyndall Effect", red light passes through this halo of small particles, while blue light is scattered sideways to our eyes. On the other hand, pure white smoke consists of particles of a few microns in size that scatter all wavelengths in all directions, while gray smoke contains particles large enough to actually absorb some of the light and colors. Different smokers produce a characteristic ratio of large and small particles, creosote and other chemicals. As will different species of wood. Pellet smokers are particularly efficient wood burners, producing modest levels of creosote, light blue or pale white smoke, and very tiny particles. Electric cabinet smokers produce more creosote and mid-sized particles. I own a pellet smoker with a few hundred hours of operation that looks nearly brand-new inside, but my electric smoker was coated with a slick layer of creosote after just 10 hours1. Small particles have the most difficult time breaking through the boundary layer. As a test, I suspended two cotton disks in a pellet smoker for an hour. Remarkably, the plain cotton disk was almost unaffected by its immersion in a deep fog of smoke. On the other hand, a cotton disk soaked in water, gently accumulated a smoky brown patina:

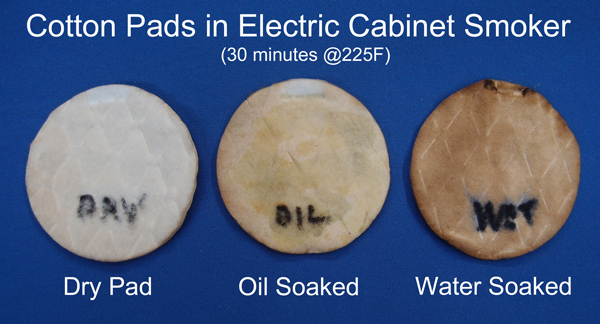

I then repeated the experiment in an electric smoker (for only a half hour), adding an oil soaked cotton disk to the mix:

The wet pad scavenged significantly more smoke, the oil pad was somewhat discolored, and the dry pad nearly pristine. Clearly, if the surface of your pork shoulder dries out too quickly, it will stop absorbing smoke particles. There are actually THREE reasons the wet pad scrubs out smoke particles most effectively. The first reason is obvious- the surface is tacky. Some smoke particles do impact the dry cotton pad, but simply bounce off. On the other hand, a pad soaked in oil or water grabs on to many of the particles during impact. But notice the oil pad is less efficient than the water pad, even though it is stickier than water, has a chemical affinity for creosote, and doesn't dry out during smoking. Which brings us to the second reason- "evaporative counterflow". Water molecules are constantly evaporating from the surface of the pad, creating an outward flow of molecules. This air current breaks up the dead layer around the meat, creating a counterflow of smoke back to the surface, drawing smoke gases in. The oiled pad did not evaporate, so no counterflow of smoke. Secondly, the wet pad is colder than the smoker. Partly because the wet cotton disk (e.g. the meat) cooled evaporatively, and partly because meat is usually smoked right out of the fridge. We can see this effect clearly by smoking two aluminum soda cans- one filled with frozen water, the other empty. After 90 minutes in the smoker, the ice has melted and the water reached 110F. Note how the frozen can is darker, and smoke accumulated preferentially on the water droplets which initially condensed on the cold-can's surface.

Which leads us to the third mechanism, thermophoresis. Thermophoresis is a force that moves particles from a warm to a cold surface. As this animation from the University of Florida Aerosol Science group illustrates, hot gas molecules gently nudge suspended particles toward the colder region, because the slower cold molecules lose out in this molecular tug of war. It also creates air currents which carry other combustion products towards the surface:

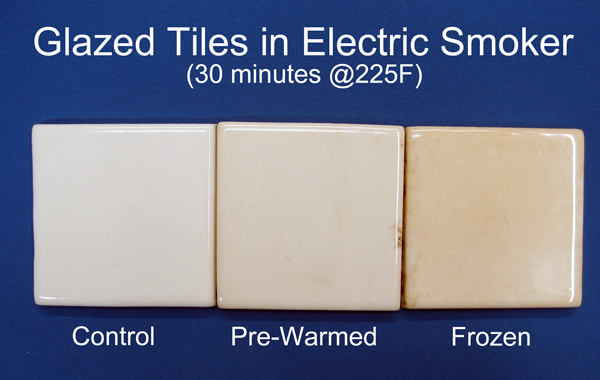

Like the soda can, eventually, the cold meat warms up. But it never reaches the temperature of the smoker, because evaporative cooling keeps its cool by stalling around 150F in a 225F smoker. This creates a smaller temperature gradient than beginning with refrigerator temperature meat, and thus the thermophoretic forces are proportionately weaker2, but still important. Depending on temperatures and time, between half and three quarters of the deposited smoke particles can be traced back to the original cold meat temperatures, and the rest to evaporative cooling and impingement. I tested the possible role of thermophoresis by placing smooth, dry, glazed tiles in the smoker. The control simply indicates the tile's original color. The "warmed" tile was pre-heated to 225F before placing in the smoker-- eliminating thermophoresis because its at the same temperature as the air. The "frozen" tile was cooled to 29F and, even without a sticky surface, captured and retained more smoke than the warm tile. Via thermophoresis.

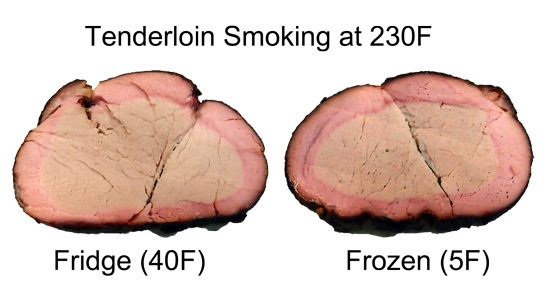

In a real smoker, the meat is colder than the surrounding air because it probably came right of the fridge before smoking, and because of evaporative cooling. Many backyard barbecue chefs swear cold meat is the secret to a thick smoke ring and more intense flavor. They are correct on both counts (though wrong if they believe smoke rings stop developing above 140F). In fact, I tried smoking a hard frozen tenderloin, compared to a piece right out of the fridge. The ice cold meat's smoke ring is a bit thicker and more uniform, especially under the meat where the smoke is normally obscured by the grating. It was also remarkably tender.

Now smoke particles aren't the whole story- in fact, most of what we think of as smoke flavor arises from gas phase chemicals, while much of the color derives from smoke particles. But, without a thermophoretic assist, few of these combustion products would make it to the surface. There are other ways to increase smoke deposition- for example, by electrostatic precipitation. Basically, the smoke is positively charged, the meat negatively charged, and opposites attract. But some of these big smoke particles are bitter. So commercial smoke houses often install electrostatic precipitaters to speed up the smoking process and improve uniformity, by charging a filter instead of the meat. This removes the acrid soot and creosote particles, while leaving the aromatic smoke chemicals free to stick to the food. You may even have an electrostatic precipitater in your hot air heating system to scrub out dust. But given the high voltages involved, I don't recommend you hack a Brinkmann together with your furnace... So what does this mean for the backyard barbecuer?

|

||

|

1 On the other hand, the pellet smoker routinely delivers a strong smoke ring, while the electric smoker never does. So particle capture is not the whole story. 2The thermophoretic force is proportional to the temperature gradient divided by the average particle temperature. Recalling that temperatures in physics formulas are referenced to absolute zero (e.g. -460F), and assuming the average particle temperature is half way between the cold and hot side, the ratio of thermophoretic forces between the ice cold meat and the stalled meat is [(225-29)/(460+225+29+460)]/[(225-150)/(460+225+150+460)]=2.9 large enough to make a difference, not so large that you can ignore smoke deposition during the stall.

|

||

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |