| g e n u i n e i d e a s | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| home | art and science |

writings | biography | food | inventions | search |

| smoke ring flavor | ||

|

||

|

May 2014 Summary smoke flavor from wood fuel:

Flavor is a matter of taste and familiarity. If you grow up nibbling on Hersey's milk chocolate kisses, you may never enjoy the intense bitterness of a 70% cacao chocolate bar in adulthood. If you start out life eating fermented bean paste smeared on rice, that pungent flavor may forever denote comfort food, instead of rotting garbage. And, while one guest may insist a charred, bloody red steak is their idea of perfect meal, another would rather gargle day-old cigarette ash. So the "right" level and type of smoke flavor is a matter of taste. Especially since many, if not most diners soak their ribs or pulled pork in a pungent-tangy-sweet-pepper sauce, demoting smoke flavor from a leading role to a mere bit player. But I do believe that some smoke flavors are more equal than others. And this opinion is held by the majority of commercial smoke operators and many competition winners- the best smoke flavor is generated by hardwood embers with an average temperature between 650F and 750F. More than a mere opinion, this position has its basis in the chemistry of wood combustion. Hardwoods are built from hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin. As each wood component is consumed by fire (in one of four stages), various chemicals are liberated. These chemicals, in the form of vapors, fine particles and soot, flow onto the meat. Along the path from fire to food, they continue to react, condense and morph in composition. Your nose and tongue are amazingly sensitive instruments. Some flavors can be detected below1 the part per BILLION level. So even tiny amounts of acrid elements can dominate the flavor and aroma profile. Below 450F, combusting hemicellulose molecules are mostly acids and various gases. None are particularly desirable on food, but by 500F most of the hemicellulose has burned away or turned into charcoal. Cellulose releases water and acids and alcohols and tars and various combustible gases. Again, not too palatable, though much of the meat's mahogany color is a result of these chemical components. And, on a more positive note, cellulose is a sugar polymer, so its not surprising to discover brown caramel colors and flavors abound. By 600F the relative abundance of tarry cellulose compounds peaks and begins to decline. Lignin is by far the more interesting ingredient from a culinary standpoint. A big messy molecule that gives wood its strength and rot resistance, bound inside the lignin molecule are the the precursors to smoke flavor, aroma and color. One is guaiacol, which is responsible for most of the smoky taste. Another is syringol, which your nose immediately identifies with fire and smoke. There are also clove and vanilla-like compounds. And literally hundreds of others. Some evaporate away in hours, some in days, others in weeks. One reason barbecue doesn't taste the same reheated.

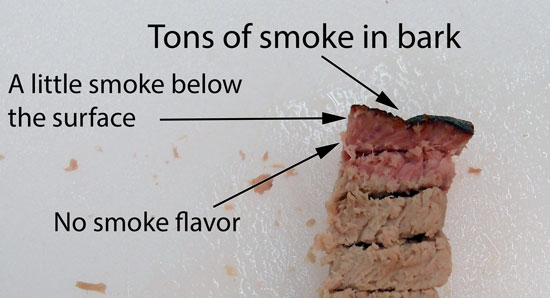

So creosote will condense on the surface of cool meat, adding a smoky though bitter note. Creosote is also water resistant- this is why you may notice the first time you try to apply sauce over a dark-orange bark, the sauce does not stick, and may even ball up in places. But, if you spritz and keep the surface moist during smoking, and herbs roughen the bark's surface, creosoty deposits and flavors are minimized. Lignin continues to decompose after 590F, but as the temperature rises above 800F, carcinogenic molecules like PAH arise. Many desirable flavor molecules are also destroyed by the heat of a more intense fire. So the best smoke occurs in this "sweet zone" of 650F-750F, where acids, tars and bitter creosols are minimized, while smoky flavors are maximized. As we discuss in the wood combustion tab, no fire burns at a single temperature, but varies from smoldering to intense to dying embers throughout the firebox. Since low temperature smoke is acrid, while the high temperature smoke is merely weak, best practice suggests building a vigorous fire which is above 650F everywhere, and thus produces the cleanest smoke. In the end, it is the skill of the pitmaster that determines the flavor profile from run to run. It's easy to create impressive billowing clouds of white smoke- just burn moist wood at a low temperature with little oxygen. And the meat will taste smoky but acrid- I find this bitter taste lingers on the tongue for hours. But some people grew up with this flavor, and to them, it signifies home and good times. Or, you can burn post oak in a roaring firebox of an offset smoker- the smoke will be sweet but very light in flavor, and might not be able to stand up to simple salt and pepper. In addition to controlling the fire's oxygen level and how new fuel is added and mixed into the embers, the pitmaster controls the choice of wood. Certainly, it is common practice to avoid long cooks with sticky resinous woods like pine. Resin contains terpenes (which are the source of turpentine), and few guests associate oil paint with good barbecue. Cedar or redwoods, which are particularly mold and insect resistant, should also be avoided in a long cook. But in small doses, or when cold smoking, these woods strike a distinctive flavor note. Every tree species contain slightly different types and amounts of lignin. Even within a species the flavor profile will depend on the micro-nutrients the tree absorbed- these minerals act like catalysts, tipping the combustion reaction in different directions. Not all oak is the same from year to year or place to place. And bark contains more nitrogen than heartwood, so it enhances the smoke ring. Because barbecue is, by most definitions, is cooking low and slow and indirectly off the heat2, most smokers limit air flow to keep the temperature and fuel consumption down. But it also assures much of the fuel is smoldering rather than burning. Low oxygen levels leads to greater soot production and less nitric oxide production. So a smaller smoke ring. Moisture levels controls how easily the smoke particles condense together, and thus how efficiently they stick and collide with the meat's surface. Seasoned wood, perhaps 15% moisture level, is often viewed as ideal. Green wood produces more smoke, but with acrid overtones. Moisture levels in the firebox (not the smoke chamber) also adjust the amount of nitric oxide produced vs other nitrogen compounds, and thus is a second contributor to the size and color of the smoke ring. More moisture, less nitric oxide. A uniformly glowing, well-vented wood fire is the goal. Some smokers on the market inevitably choke air from the fire, or are so well insulated, they consume too little fuel to avoid acrid smoke. It still is smoke, and it is good. Just not best. Once smoke ends up on the meat, it may not make it to the dinner table. At first glance, it would be surprising if smoke penetrated much beyond the surface. Smoke flavor molecules, like guaiacol, phenol, and syringol are pretty complex and large and have trouble squeezing past the dense cell walls of meat. By using color indicator dyes to follow the diffusion of chemicals from the surface, we've demonstrated that tiny salt ions might end up an inch below the surface, while much larger sugar molecules don't make it much further than a mm. To test if smoke is more like salt than sugar, I smoked a 6 lb pork butt for 8 hours until it hit 155F, then placed in the Texas Crutch for another three hours until tender. No salt, and no rub to confuse the taste buds. Just porky goodness. After resting for an hour, I sliced out this plug of pork shoulder. Each slice was 1/4" thick. I then tasted each plug, cleansing the palate between slices by sipping hot green tea. Except for the top plug, NONE of the inner meat layers had any smoke flavor at all!

I then segmented the top slice into thinner segments and repeated. While the bark was deliciously smoky, a slice without bark just under the surface, but still in the "smoke ring" was only lightly flavored (I also repeated this test on bacon- again, only the top 1/4" or so exhibited any smoke flavor. Try this at home, as long as you experiment with real bacon, not a pork product injected with liquid smoke, potassium lactate, artificial maple flavoring, ....)

In other words, just like sugar in a brine, smoke does not penetrate much beyond the surface. Normally, every bite of ribs or brisket contains a bit of bark, so your tongue is fooled into thinking the entire cut is smoky. But it's not. Fortunately, the jus collected in the Texas Crutch IS smoky. So you should blend this flavor bomb into your post-cook brisket glaze, and paint onto every slice of meat. Or let the brisket rest in the jus for a few hours. It will then carry liquid smoke flavor into every nook and cranny. Or, as is common with pulled pork, chop up the bark and mix in with the rest of the pulled meat to more uniformly distribute the smoke flavor. However, if you washed the bark off during smoking- by excessive fat rendering or spritzing, or by letting the surface dry out too early so smoke flavor molecules are deflected, your "smoked" meat will taste only like rub. Which will satisfy many diners. But not me. |

||

|

1 Some chemicals, particularly those containing sulfur, can be detected at the part per trillion level, and their flavor identified at 10 ppt. Many smoke compounds, like some creosols and organic acids, are easily smelled or tasted below 100 ppt. 2On a grill, open-pit barbecue or an ugly drum smoker, where fat drippings are volatilized in the fire, many acids, alcohols, caramels and oxidized fats particles and gases are generated, and lofted by the flame onto the food. A pleasant, smoke-like flavor that is not as strong or as persistent as those from lignin-based wood compounds, is the result. So combining smoking with a final grilling step, or smoking directly over fire, adds an extra layer of flavor. On the other hand, it may also add a second layer of mutagenic chemicals. While the science is still emerging, the higher temperature fat combustion appears to create a larger number of dangerous chemicals than indirect barbecuing- so don't breath the smoke, but do enjoy the meat.

|

||

Contact Greg Blonder by email here - Modified Genuine Ideas, LLC. |

Because the three wood components burn simultaneously, their compounds mutually interact. For example, creosote is the bitter progeny of this three way mutual relationship. A yellow, oily compound, creosote contains a mix of acids, tars and the smoky flavors from lignin. Creosote condenses at 250F and continues to flow until 150F. If you smoke above 250F, and the walls of your smoker and chimney are insulated, you won't observe creosote deposits like those in the photo to the right. Which is one reason people smoke fast and hot. But, there is always one part of your smoker below 250F- the meat, which never exceeds the boiling point of water, 212F.

Because the three wood components burn simultaneously, their compounds mutually interact. For example, creosote is the bitter progeny of this three way mutual relationship. A yellow, oily compound, creosote contains a mix of acids, tars and the smoky flavors from lignin. Creosote condenses at 250F and continues to flow until 150F. If you smoke above 250F, and the walls of your smoker and chimney are insulated, you won't observe creosote deposits like those in the photo to the right. Which is one reason people smoke fast and hot. But, there is always one part of your smoker below 250F- the meat, which never exceeds the boiling point of water, 212F.